6/27/14, Friday, concluded

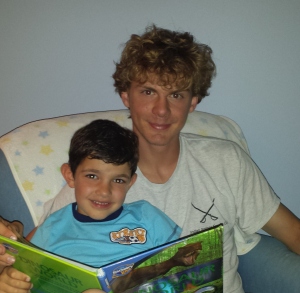

As they woke, my niece E. and nephew W. greeted us and swapped bits of travelogue. Thomas and W. went down to the lakeshore, put the canoe in the water, and worked out a rowing scheme based on sharing the one useable paddle to cross the lake.

Almost a month on the road, along with a final 22-hour push had tapped Thomas and me out. He and I both succumbed to the need for sleep and napped in the afternoon. When we woke in the early evening, Elizabeth had arrived from Memphis, her work for the week having just wrapped up. Two thirds of our family was convened–along with in-laws, niece, and nephew. Conversation ranged widely—over our two currently in the Middle East, cinema, aviation, and cars. Familiar and comfortable, the in-laws’ house felt like home, and this was a miniature homecoming. Yet being at their place was still part of the road trip, and one more leg of 230 miles remained.

6/28/14, Saturday

Thomas, W., and I woke at 6:00 to go on a flying expedition with my father-in-law R. We went to the Gallatin airport, rolled out his four-seat Archer, folded ourselves into the seats, and took off for Shelbyville. R. belongs to a flying club, which in fair weather hosts a breakfast each Saturday at a circuit of small airports around middle Tennessee. Members fly their own craft to the event for a meal cooked by members who live close by. In a hangar they serve scrambled eggs, grits, biscuits and sausage gravy, fruit salad, and lots of coffee and juice. At this gathering there were perhaps forty people, and R. seemed to know almost everyone—their lives, families, and aircraft. With a good deal of pride, he introduced Thomas and W. to several of these folks. And he spoke of his other grandchildren. “You remember my granddaughter who did her pilot training a couple of summers ago? This is her daddy,” he said finally, gesturing at me.

A veteran pilot in Vietnam, long-time C-130 pilot for the Tennessee Air National Guard, corporate pilot, and recreational flyer, R. loves flying and aviation. He is in the air whenever weather and schedules permit. About three years ago he and another flyer in Nashville embarked on building a Zodiac CH 650 from a kit. Over many months, the two-seat fuselage, two wings, and a reconditioned engine took shape in his basement. When these components were ready for assembly, they took them to a hangar at Gallatin and bolted wings and engine to airframe, connected cables, clamped in tubing, and secured wiring. Without fanfare, one day last year his associate posted a You-Tube video of R. taxiing around the runway. In a few more months, again without fanfare, we got an email from him saying he had flown the plane. Since then he and his associate have flown the “experimental plane” over fifty hours, the minimum time they must operate it in the air before taking passengers.

We walked the tarmac and saw planes single-seat to six-seat, factory-made to home-made, and 1938 vintage to 2013. One of the most surprising flying machines was a gyro-plane, which was wingless but had a large passive rotor on top reminiscent of that for a helicopter. As the plane taxied under the power of a horizontal-axis propellor the rotor caught the wind and turned, providing lift. All these folks (mostly men, truth be told) shared the sheer joy of being aloft, of being around others who enjoy flight, and of maintaining or building airborne conveyances. The concentration of satisfaction was palpable.

On the way back my nephew sat in the “shotgun” seat, and once we were at a cruising altitude of about three thousand feet, my father-in-law said, “OK, W., I’m handing the controls over to you. For the moment, just pick a point out on the horizon and fly toward it.”

The color drained from my face, but I stayed quiet, confident that if my nephew made some sudden motion with the yoke or pedals that my father-in-law was there to right the plane. He flew us fairly steadily, but I sensed what the altimeter corroborated: we were climbing. I’ve heard about stalling an aircraft with a steep climb, and that unfortunate image was on my mind. R. said, “Push in on your yoke a little,” and W. brought us back down. We climbed again, and once more R. had W. bring us back down. In a few more minutes, my father-in-law said, “I saw that rain earlier, and I thought we might have to fly through this little storm…”

I looked at Thomas beside me, and his jaw was tense. I looked at my knuckles, and they were white. Then a small heave to the left and a steadier motion of the small plane told me R. had taken back the controls and was entering an approach pattern for the Gallatin airport.

Three thousand feet the air, everything on the ground is visible—at least when it’s clear—and yet identifying specific landmarks is surprisingly difficult. R. was turning the plane for a landing from the north, he said, but I did not immediately see the landing strip. As we were in a steep turn, I had to look “up” to see it. When he let off the throttle and we descended more rapidly. “There are five lights in a row beside the runway. When we’re approaching at the right glide slope, two of them will appear white and three will appear red,” R. said.

I found the lights and saw all white. Then one turned red, and then another, and then another. They stabilized, and in a few more seconds we touched down. I breathed deeply and was very grateful—for good company, a great breakfast, and terra firma under my feet. R asked if we were interested in going up in the Zodiac. Son and nephew were game, but clouds, rain, and wind were moving in, so that put an end to flying for the day.

6/29/14, Sun

R. took Thomas and W. for a flight in the Zodiac, but the air was rough enough to elicit airsickness for the boys.

Charlotte sipped more half-and-half and ate patties of dog food. She was still very weak and had to be led out to the yard. Blind and deaf, she responded only to her back being rubbed and gentle tugs on her collar. She had stumbled on the steps to the back porch and abraded her left elbow, so Elizabeth and I cleaned and wrapped it with gauze for the extended time Charlotte was lying down.

I told my in-laws I would have to leave Monday to tend to several pieces of business I’d left hanging at the beginning of June. During the week Elizabeth would be in charge of tending Charlotte, and at the end of the week when I came back to pick up Thomas, we would re-evaluate.

6/30/14, Monday

I set out for a solo distance drive, an undertaking I’ve not made in over a month. While I would be in Birmingham, Thomas would stay at the grandparents’ with his cousin for the week, and then I would pick him up the weekend of the Fourth of July.

I listened to a few podcasts on my I-pod, but then the battery died. Then I attempted to listen to the radio, but I was NPR-ed out, as well as country-ed, pop-ed, and oldies-ed out. As the car rolled southward on I-65, so my outlook went south as well.

Leave-taking is difficult, but returning home is even harder. Job, family, house, and personal sense of responsibility all have their claims until you hit the road to leave home. Four weeks ago, the first afternoon of Thomas’ and my road trip, I had already entered the world of the highway. When we had been out about three days—somewhere in Texas—I was completely in the mode and felt I could continue indefinitely. Now, driving back to Birmingham, I wondered about the house sitter and whether she’d tended everything. The prospect of resuming work on the deck was daunting—railings remained to be completed, and that would require a lot of endurance, balance, flexibility, and perseverance in the heat and humidity. I would be working alone, and the progress would be about one fourth the rate as when someone else helped.

In the morning I had called my doctor to make an appointment with a specialist about a painful and worrisome condition that had persisted for several days and that I thought might be the beginning of something serious. Anxiety over it had begun to cloud my days. Though the scheduling nurse had said the earliest the doctor could see me was Thursday, I was formulating a plan to call her again in the morning and ask that they move me up if they had a cancellation.

My driver’s license had expired on the 28th, and while Alabama has a grace period in which it can be renewed, I was not certain Tennessee would honor that, so I was especially careful not to do anything on the road that might require a THP—or AHP for that matter—representative to look at it. I was dreading the renewal process, because I had heard in the wake of the Jefferson County bankruptcy, people stood for hours in line at the courthouse and satellite offices. But it had to be done.

When I returned, the house was fine, though there was evidence I would have to deal with a rodent problem. I had lots of dirty laundry from the trip. The fridge was clean but empty. In the back yard the carpentry project cried out for completion. Virginia creeper, weeds, privet sprouts, and honeysuckle had invaded fence lines and would require pulling and cutting. My desk was strewn with the same heterogeneous papers as when I’d left. The postman had delivered a crate of accumulated mail at the back door, and it probably contained an overdue bill. As I was the sole occupant of the house for the next few days, every bit of action and attention had to come from me alone. Hunter S. Thompson’s titular phrase fear and loathing described my state of mind, and I sat in a chair for a long time with my face in my hands.

As I pondered all I faced, I realized this death by a thousand cuts was the time- and space-distributed equivalent of a collision with a buffalo. Each by itself is a micro-disaster, and integrated over spatial and temporal coordinates, these loathsome, inconvenient things can sum up to a macro-disaster such as a stroke or automobile accident. If I took all the terror and loss tied up in that moment of contact between 2000-lb beast and 12-year-old car with payload, and I broke it up into little bits and inserted the bits into various facets of, say, a fortnight’s worth of ordinary suburban life, then the net result might look something like what I was facing on this return. Or equivalently, if I took the two-weeks’ worth of vicissitudes, any one of which without attention could metastasize to something bad, and I somehow bundled and synchronized them all to occur at once, then I might have the equivalent of a major trauma.

The atmosphere is continually bombarded by rocks from space, and the vast majority burn up as meteors. Occasionally one makes it all the way to the ground, becomes a meteorite, and frightens Russians or come through the roof of a house in Sylacauga. Economists talk about a risk-free rate of return on an investment but hasten to say that no such thing actually exists. One of my former colleagues was fond of saying, with an ironic grin, “You know, there is a 100% correlation between those who have died and those who have lived.” Imitating a naive user of statistics, he went on to say, “Living causes death….” The point sinking in on me, and not for the first time in my life, was this:

By living we put ourselves at risk. Living causes choices, and making no choice is still a choice. Awareness of a risk is evidence of desire within, and as long as desire exists there is value in life.

I recalled a snippet of a poem set in an anthem—perhaps by the medieval mystic Hadewijch of Antewerp—expressing gratitude for desire itself. From her verse I glean something fundamental, that wanting in and of itself is the nub of life and that physical and spiritual converge in it.

My inner voice was talking to me now: Stalling or being paralyzed by the unpleasantness or sheer number of to-dos is exactly the opposite of what Mary Schmich counseled in her “Sunscreen Speech” in the Chicago Tribune years ago: “Each day do something that scares you.” Go to the doctor and find out exactly what is going on. Go stand in the damned DMV line and get the new license. Put a sliver of cheese in the trap and set it next to the hole where the vermin go in and out. Grow a pair, dude. Concentrate on one thing at a time. Finish it and move on to the next. The road trip never ends.